The Steel Frame of India: Navigating the Structure, Branches and Hierarchies

18 Nov 2017 0 comment(s) Research Essays

First published: June 2016

This Revised and expanded version: November 2017 (first published on wrodpress blog-site)

Kennedy School Review- 2011, the annual magazine/journal of Harvard Kennedy School published an essay by me on the issue of reforming the organized cadre-based higher civil services in India (what we in India popularly identify as IAS, IPS and others). Writing and finalizing the essay was an experience in itself, as what I initially wrote was well beyond the word limit, and I had to go through several iterations before it was finalized. My editor was truly merciless, not ready to listen to me, and scoring out whatever I had written with so much of passion! In the end, though the essay was much curtailed, I was happy with the result. It was a short and crisp piece, and in the process I learned too.

In my previous essays, I have repeatedly pointed out that the institutional and governance reforms are one of the crucial steps which our country needs the most at this juncture to move to the next level of growth path. In that sense, civil services reforms are now the 'binding constraint' shackling the growth of our country (and in particular my state - Bihar).

In these essays on reforming the higher civil services in India, I propose to follow what I have written in 2011 for Kennedy School Review, with suitable addition, much expansion, revision and elaboration. And I will be discussing freely various issues which have rusted the ‘Steel frame’ today.

I must point out that the original essay was written for US/non-Indian audience, and therefore, things were explained starting from the basics. In that sense, this essay may appear somewhat familiar to many of my Indian readers in general, and to my civil servant colleagues in particular, as it is concerned with explaining the structure and other characteristic features. Nevertheless, I would urge them to go through it patiently (this essay, now in the revised version, is 6700 words long), as I think, it contains useful insights and subtle points. WordPress.com statistics tells me that a significant proportion of my blog readers are from outside India, and therefore, I am maintaining the basic explanations.

It is difficult to structure the essays in advance, but tentatively, I would be covering the following issues in this and subsequent essays:

- The Structure and 'Services'

- Induction and Recruitment

- Meritocracy or Mediocracy?

- 'Services' - Roles, Functions and Reorganization

(Let me note with the hindsight, in this revised version, that I could not maintain the structure as above)

So, Here we go....

1. Getting into World’s Best Universities is like a Cake-Walk in comparison…

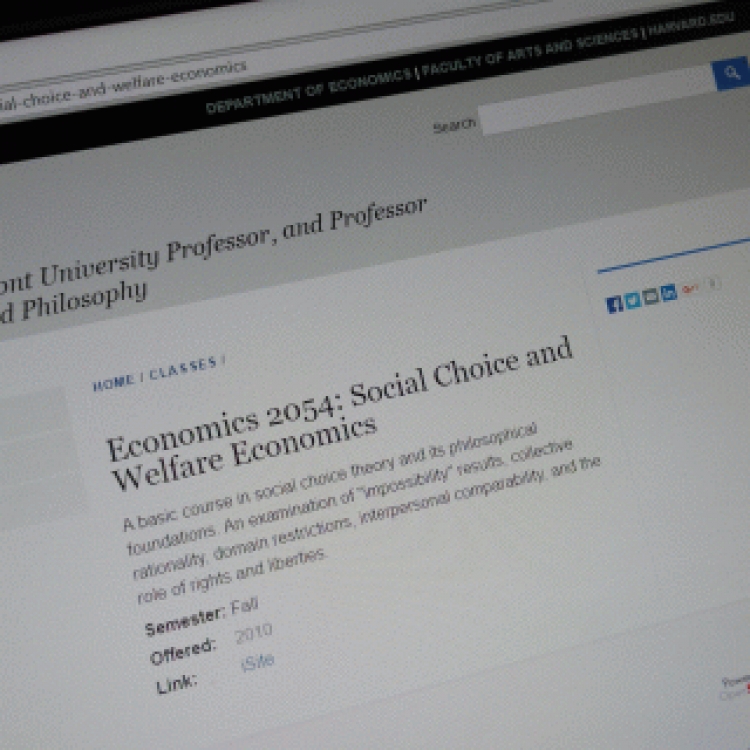

Have we ever wondered as to what is the most difficult and most competitive selection process in the world for getting a job or a seat in a university? Most probably, it is India's Civil Services Examination which recruits permanent higher civil servants for different branches of the federal as well as state governments' bureaucracy. One of my professors at Harvard University has rightly observed that the Indian civil service is full of officers who have passed an entrance examination and selection process that makes getting into Harvard look like a walk in the park (Pritchett, 2009)!

However, I think that the comparison cannot strictly be made. There are various factors which make it like comparing apple to oranges. First, comparing a competitive examination for job with that of a process of selection for admission to a university degree is not in order. Next, socio-cultural and economic situation in USA and India are completely different. Clearly, there is a huge resources and opportunity deficit in India, which has a bearing on educational structure, job and career prospects and resulting choices and preferences of the youth. Further, we in India hardly make any ‘self-selection’ while taking competitive examination and it is quite common to find large number of non-serious candidates appearing in UPSC and other competitive job examinations, often without much preparation, and largely with the sole motive of getting into ‘any’/’some’ job for a living. Obviously, this is not the case in USA.

Furthermore, within India, different regions display different preferences of youth towards their career. The very strong preference and attraction towards civil service career is more pronounced in cow-belt in general, where huge number of young spent their precious productive years appearing in competitive examination, sometime without much preparation or thought. I sometime think that it is a favourite pass-time of Bihari graduate! On a serious note, lack of industrial and commercial development and progressive decline of agriculture resulting into dearth of employment opportunities, coupled with socio-cultural preference for government job (which in our country is secure, low risk and mostly keeps paying without any consideration to performance) is a driving factor towards this mad-rush for taking competitive examination to find any type of government job.

2. The Gruelling Selection Process: Risks, Rewards and Outcomes

Consider this: The latest figures (available at the time of original essay in 2011) shows that every year around 380-400 thousand young Indians compete through a fair, open, meritocratic three stage intensely competitive examination process for around 600-800 vacancies in higher bureaucracy - making a selection ratio of around 1 in 600 candidate (UPSC, 2010)! The examination has rightly been called not a 'selection' but a 'rejection' process! In India, higher civil service is one the most popular career options for some of the brightest young Indians graduating from universities - with degrees in management, engineering, law, science, social science, liberal arts, medicine and what not, with widely varying social, economic and regional background (Barik, 2004). If looked purely in terms of monetary rewards, a career in civil service would not compete very favourably with other careers in business management, consulting, software, technology or medicine. Despite this, it attracts some of the best talents in India from all sections of the society mainly because of highly rich job content and diversity of responsibilities (at least for some), social recognition and prestige associated with being in civil services, and an opportunity to work in areas of development, provision of public goods and general administration of the country. In fact, a person joining the career bureaucracy can aspire to reach the highest level of government machinery just below Ministers (political executives, who are elected members of Parliament) as, contrary to USA, political discretionary appointment of higher executives by Ministers does not exist in India.

The recruitment for civil services are managed by an independent constitutional body called 'Union Public Service Commission' which conducts annual examination and personality tests for selecting suitable young candidates. Any Indian with an undergraduate degree in any academic discipline, between the ages of 21 to 30 years can appear for the first stage called the 'preliminary' examination, at the most 4 times. However, there is positive discrimination for socially disadvantaged sections of society in terms of higher number of attempts and higher cut-off age limit as well as certain quota of seats reserved for candidates belonging to these sections of society. If selected, she can then appear in the 'mains' examination and on further being successful; she is called for an interview and personality test. The final selection is made on the basis of performance in mains examination and personality test whereby an all India merit list is finalized and successful candidates are announced.

Since I wrote the above paragraph in 2011, the selection process has undergone some changes, the ‘preliminary’ examination is replaced by what is now called ‘CSAT – civil services aptitude test’, but essentially, the nature, content and difficulty of the examination remains the same. Further, the number of candidates appearing for the examination has continuously been increasing year after year despite claims from various quarters that the attraction of higher civil services is waning with the overall growth of the economy and increasing opportunities. There might be some truth in this claim too - and we need deeper analysis of this - especially with respect to the socio-economic strata of the candidates taking up the examination and also examining the variations in regional, rural-urban and educational background and their time series movements

Successful candidates are allocated to different 'branches' of the service on the basis of their rank in merit list and their choices. Every year, successful candidates receive wide public attention, with their interviews coming in national, regional and local print and electronic media, they being invited for talks and for providing guidance to the aspirants etc. The wide popularity of civil services has helped development of large number of coaching/guidance institutions all over India, and there are localities in metros like Delhi which are buzzing with students living in small rented hostel-like cramped private accommodations preparing for intense and exacting selection process. Alas! Only a small fraction of them ultimately get successful and for others, the failure (in many cases, after investing 3-4 precious years of their youth) often haunts them for quite long, though they ultimately have to settled for alternative careers.

I would like to further highlight the piquant 'uncertainty' and 'risk' characteristics of civil services examination, which makes it a very interesting situation to examine from risk analytics perspective. The uncertainly involved in selection are very high – as I have already pointed out – only 1 in 1000 or so candidate gets selected through the gruelling process and one iteration of the process takes one year. General candidates are allowed 4 chances, up to the age of 30 years. I have known large number of my friends and others who have invested 4 precious and most productive years of their youth preparing for civil services examination ultimately to be unsuccessful. Some of them got through other competitive examination and have been redeemed to that extent. Some, after failures opted for other types of private sector jobs, and some became entrepreneur and businessmen. However, some of them are still not well settled and in that sense have paid heavily by taking this risk.

But the main point I want to make here is something different. It is about the contrast in risk before and after selection. Take this - I have hardly heard of any civil servant who has been fired for non-performance! Once you are selected, your career is almost risk fee – whether you work or not, whatever be your performance, you will keep on getting promotions (mostly) on time, keep moving up in the hierarchy and your salary will keep getting higher and higher with each promotion. Ok… I may be exaggerating a bit. But more or less, the situation is not very different from what I have described. We often hear that donkeys and horses are treated the same in government in India and that's the real point. The subsequent parts of the essay will talk about this issue, and therefore, we stop here with my concluding observation on risk in civil services examination:

I see a very interesting application of economic concept of risk-aversion and inter-temporal preference for risk in this situation and a deep insight into why so many take that risk: take very high risk for 3-4 years in the beginning to get an almost-risk-free life for subsequent 30-35 years.

3. Governance and Permanent Bureaucracies

Governments have been one of the most important institutions of our society ever since the human civilizations organized themselves in recognizable and manageable groups. In today’s time, the role and responsibilities of government is immense for organizing and managing a society on mutually agreed principles of humanity and a civilized society bound by principle of freedom, justice and liberty and independence to individual. With such responsibilities, national and sub-national (regional) governments in different countries are often gigantic organizations, largest employer, and are usually organized into different ministries, line departments, and executive agencies carrying out the myriad functions of national administration and security, maintenance of law and order, raising of revenues and provisioning of public goods with varying level of involvement in economic and social development efforts and in facilitating and regulating the markets, industry, trade and commerce. Whether the scope for state activities are large or small, which depend on historical, social, cultural, economic and political factors, modern nation states need public institutions, administrative structure and resources to carry out even the minimal functions of governance.

Typically the government institutions are bureaucratic, which are often characterized as ill suited to cope with its task and purposes - as they are too big, powerful, hierarchical, rule-bound, indifferent to results, inefficient, lazy, incompetent, wasteful, inflexible, unaccountable (Oslen, 2008) and what not! However, this perception often fails to see the fundamental difference between a public and private organization - the most crucial of them perhaps being the accountability to the public at large and public service nature of administration. Further, bureaucracies have been reinventing themselves, and despite such strong criticism, they have not only survived but also have grown and evolved in many respects (Simon, 1997). And bureaucracies have been reinventing and restructuring themselves, almost continuously, in many countries of the world, and certainly they are in that sense, at the world level, a dynamic institution, not an ossified and archaic structure. Without further going into examining bureaucratic reforms and issues like de-bureaucratization, post-bureaucratic forms, New Public Management etc., it may in short be noted that in past two decade or so, there has been perceptible change in the way government departments and bureaucracy operates and there has been improvement in some crucial areas.

4. Indian Bureaucracy: Structure and Size

'Steel Frame of India' was the phrase late Jawaharlal Nehru used to describe the organized civil service of India in general, and to the IAS branch of senior civil service in particular. Though it was a British legacy and Nehru was skeptical of it in the beginning, he came to appreciate that a highly qualified, professional and meritocratic civil service institution would, perhaps, be an important factor in making a successful transition of India from a backward nation to a prosperous country. As it turned out, though the transition may not yet has been achieved after more than 65 years of independence, the senior civil services, as a professionally managed cadre of bureaucrats has evolved as one of the pivotal institution of the democratic India. It has even been identified as one of the important factors behind the deepening of democracy and consolidation of the idea of India (Guha, 2007). In the parliamentary democracy of India, where the political executive come and go through regular general elections, the executive civil service is permanent providing much needed continuity, knowledge pool, expertise and professionalism to better manage a vast and diverse country. Though responsible and answerable to political executive, the administrative and institutional structure of civil service is not dependent on the whims and fancies of the political class, thus providing a fine example of checks and balances in a modern governance structure, together with independent judiciary and free press.

Senior civil servants of these organized branches are not only administrators of India - they run district/local administration, collect revenue and taxes, maintain internal security & law and order, run school education and public healthcare facilities, execute developmental programs, manage foreign relations, regulate the markets and other economic institutions, even run railway and broadcasting corporation; but are also policy makers - economic, social and developmental - manning almost all the higher level posts in federal and state government ministries. In a sense, they are virtually present everywhere in national polity and administration. Their roles and responsibilities get augmented in the developing country setting of India.

It would be imperative here to identify and place the structure I am talking about in proper perspective and setting. I am and will be mainly discussing the top layer of organized civil service of India – which hardly forms 1% of the total number of permanent civilian employees of government - but these officers run the government and provide the leadership to the organizations/departments of the government.

Let us have some more data about the size of government in India. Governments in India – I am using the plural to indicate that there are two levels of governments in India – Union or Central of Federal government and then State or provincial governments - are the largest organized sector employer, employing as much as 10.5 million people directly as civilian employees (that means it excludes the armed forces), most of whom are permanent. This is around 1% of total population of India. It may also be noted that this number does not include teachers employed in public education system including the higher education in universities. Going further deeper, out of these around 10.5 million people, central government employs around 3.7 million persons. Out of this, around 1.5 million are with railways and 0.4 million are with posts alone. All 29 states governments in India together employ remaining around 6.8 million persons, in various line departments, executing agencies and other organizations.

Out of 10.5 million government employees with Central and State government, the senior management level (which may be equated with what in India is called Group A employees) forms only around 1% (around 100,000) and out of this, around 40% constitutes what is called ‘senior civil services’, with which we are concerned here. The remaining 60% of so constitutes what generally is called managerial/professional cadre of 'technical services' like medical doctors, scientists, engineers in roads, buildings, public health, communications, scientific and research and infrastructural departments, etc.

To be more specific, the civil service institution in India is organized on hierarchical lines with well-defined structure, process, roles and responsibilities as well as salary and perquisites. In governmental structure, four broad hierarchies of employees are defined. They are called (quite unimaginatively) group A, B, C and D level employees, with D being the lowest. Within each group, there are again hierarchies and levels. Generally group A and B category posts are managerial level positions, and Group C and D categories provide the crucial executive and clerical support. However, recently, government of India has decided to abolish the lowest group D (in fact this group has been merged with group C) and has also decided that it would henceforth be employing only people with at least high school education (Government of India, 2008). The decision to recruit people with only high school (10th grade) education (and outsource jobs which require lesser or no education) has been protested and criticized, on the grounds of it being iniquitous and elitist, as it leaves the less educated to the vagaries of unorganized sector and private sector employment, which is widely (and correctly) seen as exploitative. The argument has some merit as access to universal school education in India is still far away - and children have widely differing opportunity for access and quality of schooling which is closely correlated with their socio-economic status.

In terms of numbers, as we have seen above, group A forms around 1% of total employees, and are mostly the top management level functionaries. Further, around 10% forms group B, around 55-60% are in group C and remaining 30-34% are in group D (Ministry of Labour, 2003). Recruitment of group B (and some group C) federal government employees is done by another national agency called ‘Staff Selection Commission' through open competitive examination process for different ministries/department. In case of state government civil services, all the states have their own ‘Public Service Commissions’ which recruits civil servants for group B and C, mostly through open competitive examinations. Recruitment of group D (as well as group C) employees is generally decentralized to respective departments/executive agencies.

There is a complex, though structured way of organizing and managing these different categories of employees. Direct recruitment of young people through open competition examinations is made at entry level of each group A, B and C. In addition, at each entry level, some proportion of recruitment is made from amongst promotion of employees belonging to immediately lower level on the basis of seniority, which varies anywhere from 25% to 75%. The idea behind this is to have a mix of not only young people but also experienced people at all three/four levels in the hierarchy. This structure coupled with permanent employment and seniority based promotions also ensures proper career progression and promotional opportunities.

5. Branches of Senior Civil Services: Preferred and Leftovers

As I have pointed out, I would be discussing and analyzing only the highest level of civil services (called group A, and also identified as Steel Frame of India) in detail. There are many 'branches' of the higher civil services, which should not be confused with line or functional departments, as they often transcend them. Branches, called 'services' in India, are organized cadre of civil servants (officers, not agencies) grouped largely on the basis of broad functional areas. There branches are organized as closed group and form a cadre of permanent civil servants, who perform and work in some particular functional area, are organized in hierarchical fashion, get promotion largely on the basis of seniority, do compete among themselves, and where entry to outsiders in not allowed.

Thus, we have services named Indian Administrative Service (IAS), Indian Police Service (IPS), Indian Revenue Service (IRS), etc, members of each of which generally spend most of their career in the respective functional areas in different line departments and executive agencies as well as in policy making ministries (except for IAS – who are considered generalist and span a wide functional domain). Although, the service branches are not to be equated with a particular department of the government, many of them do spent most of their career working in one department. Before taking up this issue and delve deeper into idea, logic and reform of branch structure of ‘service, it is important to understand the structure, organization and function of branches.

Table below gives a snapshot of the various services and their broad functions. The list is not exhaustive, as in fact, there are around 25-30 different 'services' branches totaling to around forty thousand officers. Some of them are very small in size, created for some specialized functional requirements. IAS is the most prominent branch, being in charge of virtually all the state government functions and widely present at federal government ministries. IAS, IPS and IFoS are assigned to various state governments and work in state level line departments in areas assigned to states, other services are being managed by federal government and are performing functions assigned to federal government in accordance with division of power enshrined in Constitution of India.

As can be seen from the table below, except for few well know service branches, there are other services which have been created for specialized purpose and are confined largely to a ministry or function. These services are not well known, not much preferred by the candidates appearing in the examination (IAS being the most preferred choice, followed by IFS, IPS and now IRS too, generally in that order). In a sense, all those candidates being allocated to less preferred services face a vastly different career prospects, responsibilities and exposure, and future outlook, and it is an important issue which I will discuss in detail later.

In connection, I might point out the hegemonic position of IAS vis-a-vis other services, and the resulting widespread discontent in other services. IAS is organized as a generalist service, occupying top level posts in most domains and is inherently different from other services, which are specialised in nature. However, since all of them are recruited through the same examination process where a marginal difference of few marks has played in the allocation of different branches, and where all branches are in principal have the same rank and pay, this real difference in career profile of IAS and non-IAS is all the more resented. It is an important issue and it requires a detailed treatment, to be taken up by me in a separate essay.

Table 1: Main Branches of the Senior Civil Services in India

| Branch/Services ** | Apprx. Nos. | Main functions/domain |

| Indian Administrative Service (IAS) | 6000 | The most important and most widely known service. They are responsible for district and local administration, State level general and developmental administration - please note that in India, most of the administrative and developmental functions are performed by states, and thus IAS officers work at leadership roles in vast array of functional domains from healthcare to engineering to transport etc. They also work at senior position in policies, regulations and management at Central government organizations. |

|

Indian Revenue Service (IRS-IT) (IRS-CE) |

8000 |

Revenue collection of central government – which is mainly income tax, customs duties and excise etc. In fact, there are two revenue services, ie, two branch - Income Tax (IRS-IT), and Customs & Excise (IRS-CE), with no movement across these two branches. These are two different services. It should be noted that IRS officers do not man state tax department (VAT or commercial taxes, and now GST). Further, the huge size of these two services compare to others is a distinctive feature. |

| Indian Police Service (IPS) | 5000 | IPS officers are responsible for policing, maintenance of law and order, internal security, public safety, public order and peace, crime, investigation and intelligence, supervision of para-military forces, disaster management and public safety. IPS is another high profile and very popular service, next only to IAS in terms of importance, prestige and visibility. |

| Indian Forest Service (IFoS)@ | 2800 | Environment protection, forest and management of flora and fauna, mainly at state and district governments. IFoS officers also work in good number at central government ministries, especially those concerned with environment, climate, forest, wildlife, energy etc. |

|

Railways Services : IRTS, IRPS, IRAS |

2800 | There are three services branches for running the huge Indian railways. These three services of railways are responsible for management of civil functions (as opposed to technical/engineering ) of the railways operations; three branch services – Indian Railway Traffic Service, Indian Railway Personnel Service, and Indian Railway Accounts Service, called IRTS, IRPS, and IRAS, in short respectively. |

|

Accounts Services: ICAS, IDAS, IPTAFS |

1200 | Accounts, Treasury and financial management of Federal government; branches - Indian Civil Accounts Service, Indian Defence Accounts Service, and Indian Post and Telegraph Accounts and Finance Service. |

| Indian Audit and Accounts Service (IAAS) | 800 | Constitutional independent auditor of the government - central as well as states, also management of accounts of state governments |

| Indian Foreign Service (IFS) | 700 | Diplomatic and foreign relations, in-charge of foreign ministry, embassies, consulates etc., and responsible for protecting and advancing India's interest in the world |

| Indian Postal Service (IPoS) | 600 | In charge of India postal organization |

| Indian Information Service (IIS) | 500 | Looking after Information and Broadcasting ministry, in-charge of Doordarshan, Air India and similar other organization |

| Indian Trade Service (ITS) | 400 | National and International trade and commerce – regulation and promotion |

| Indian Economic Service (IES) @ | 700 | Economic management, economic analysis and policy, present in various federal ministries as economic adviser |

| Indian Statistical Service (ISS) @ | 600 | Data collection, analysis and dissemination. Mainly in central statistical organizations |

| Indian Defence Estate Services (IDES) | <500 | Managing defence estate and properties |

| Central Secretariat Service (CSS) Gr. B | <1000 | Group B service running all the ministries at central government, mostly below IAS |

| Delhi and Andaman Nicobar Civil Services (DANICS) Gr. B | <400 | Group B services akin to IAS for Union territories, including Delhi |

| Delhi and Andaman Nicobar Police Service (DANIPS) Gr. B | <400 | Group B service akin to IPS for Union territories, including Delhi |

| Source | Compiled from Information available at Department of Personnel and Training, Government of India website, www.persmin.nic.in |

| @ | Strictly speaking, these services should not be included in this list as there are separate specialized examinations for selection into these services (though the examination is conducted by UPSC only). However, they are still included in the organized Group A civil service by Government. |

| ** | The above list is not exhaustive, and there are few more services with small cadre, which have been created by Government of India at different times. Further, the number of officers is only approximate, and the reality may be slightly different, especially in case of smaller services for which I have used < sign. The last three services in the table are Group B services, which generally are junior to IAS, though are recruited through the same examination. |

I am also leaving out a large section of 'technical services' from my discussion, which is again in itself a large group of different 'technical' (mainly engineering) branches like Indian Railway Engineering Service, Indian Telecom Service etc. They manage most of the technical function of the government, but are supervised on top by mostly IAS officers, which is again a contentious issue. Traditionally and officially, they are not considered as a part of 'Civil Services'.

Distinction may also be made of what is called three "All India Service" (comprising of IAS, IPS and IFoS) and "Central Services" comprising all other branches. The basic feature of this distinction being that All India services work mostly with state government (though also with Central government) whereas Central Services officers work exclusively (though there may be exception) with central government organizations/ministry. I am not entering into the merits or demerits of such a distinction, which will be take up later on.

As can be seen, except for few well know services, there are other services which have been created for specialized purpose and have been confined to a ministry. These services are rarely known, not much preferred by the candidates appearing in the examination (IAS being the most preferred choice, followed by IFS, IPS and now IRS too, generally in that order). In a sense, all those candidates being allocated to less preferred services face a vastly different job prospects, responsibilities and future outlook, and it is an important issues which I will discuss in detail later.

Nevertheless, I might point out the hegemonic position of IAS vis-a-vis other services, and the resulting widespread discontent in other services due to this. IAS being generalist service, occupying top level posts in most domains are inherently different from other services, which are specialized in nature. However, since all of them are recruited through the same examination process where a marginal difference of few marks has played in the allocation of different branches, and where all branches are in principal have same rank and pay, this real difference in career profile of IAS and non-IAS is all the more resented. It is an important issue and I will be saying more on it later.

6. ‘Homo Hierarchicus’

I feel this essay would not be complete without discussing the love of, even obsession with, hierarchy, place and positon, which we Indians have, and which I find reflected in the way Indians have organized and structured their bureaucracy.

As pointed out earlier, separate branches of civil services act as separate 'cadre' for the purpose of service management like seniority, career progression, promotions, performance management, postings and rotation etc, though there is also an underlying structure to maintain parity among services in such matters. Promotions are mainly based on seniority, with the condition that an officer has been performing above a certain minimum benchmark - judged on the basis of her annual performance report prepared by her superior, and has not been found involved in corrupt practices or unfit due to other reasons.

To an outsider, what is remarkable is the immutable hierarchies in the structure. There are 'grades' in the hierarchy across different services with stipulation of minimum eligibility in terms of number of years of service rendered to be eligible for promotion to that level. However, the 'designation' varies depending upon the organization, ministry and the level of government (federal or state) a bureaucrat is working for. These hierarchies of career progression are functional with different levels of administrative responsibilities and it is possible to identify these with Henry Mintzberg’s famous Five Component Model having levels of Junior, Middle and Higher Management levels along with Strategic Apex (Mintzberg, 1979), though the number of levels in India system appears to be too many.

It is interesting to note here French philosopher Louis Dumont’s famous phrase popularized by his book titled ‘Home Hierarchicus’ – describing the ingrained basic nature of Indian society and its penchant for hierarchy (Dumont, 1981). The reference to notorious caste system was obvious. The same penchant seems to be playing a part in the demarcation and division of different levels as ‘grades’ in a strictly hierarchical terms, with stipulation of eligibility criteria in terms of number of years of service, movement upward (or even downward) restricted by rigid rules etc. Further, this promotion system operates like a long queue, wherein the queue is formed the day one entered in the service branch, which fixes her position in the hierarchy, and then all officers move forward strictly as per their position in the queue, with no jumping allowed. What is distressing is to note that how the hierarchy has been designed as s rigid and closed structure, with little leeway and flexibility for identifying merit, performance and talent and even exceptional circumstances. In some senses, there might be some benefits of an organized and structured system, but often in reality, these result into fomenting all kinds of bottlenecks and inefficiencies. An obsession with the structure itself, to the detriment of its intended goals, results and delivery, is a good example of being bogged down persistently in ensuring fair ‘means’ without ever reaching the intended ‘end’.

Let me present a simplified structure of hierarchies in the senior civil service. The table below gives a highly simplified and stylized division of grades and hierarchy in the higher civil services. It may also be noted that there are separate hierarchy for lower level (what is called Group B and C posts) civil servants too, which is not part of my discussion here, and therefore, is not shown in the table below.

Let me explain the information. The standard terminology of ‘grades’ is what the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT) in Government of India prescribes and defines. It categorizes the hierarchies into different grades, and there are as many as eight grades in group A category itself, which is supposed to be the leadership level consisting of around 1% of total civil servants/employees in Government of India. Eight hierarchical grades in the leadership levels are certainly too many, and any organization with such structure would be bound to be inefficient, excessively bureaucratic and stifling. However, the situation is not as bad as it appears, because all these eight levels are not strictly hierarchical in terms of reporting. So, the reporting hierarchy is generally four – which is achieved by creating non-reporting grade levels, and the promotion to these levels is called ‘non-functional’. These non-functional levels generally appear alternately in hierarchy. In that sense, the promotion is largely notional, with the officers promoted continuing to do the same (level) of work, reporting to the same higher level, and supervising the same team of people. For example, in the table below, movement or promotion from Junior Administrative Grade to Selection Grade are non-functional, whereby Deputy Secretary does not report to Director, but both of them report to Joint Secretary. Further, Joint Secretary and Additional Secretary are also mostly non-functional, but it is not universally so. These are ministries and departments (mostly large ones) where there is a reporting/functional hierarchy between Joint Secretary and Additional Secretary. In the table below, the IPS hierarchy shows this too, wherein two or more rows of grades are merged. Similarly, in the case of IAS, the officers can be District Magistrate while being in any of the grades of STS, JAG and SG.

The lowest grade, JTS, is the entry level grade for group A civil servants, where they do not spent much time. By the 4th year, they enter into STS grade from where leadership assignments and responsibilities for them start. It should be noted that out of the four years in JTS, almost two years are spent in training at LBSNAA and various specialized national training academies for different service branches.

Table 2: Stylized Grades and Hierarchies of Senior Civil Services

| Grades | Year Scale (^^) | Govt. of India Standard Designation | Pay matrix level | State govt. designations (mostly for IAS) (##) | IPS designation (#) | IRS designation ($$) | |

| Apex Scale @@ | Sel. | Secretary/ Special Secretary | 17 | Chief Secretary/ Addl. Chief Secretary | Director General | Pr. Chief Comsnr. | |

| Higher Administrative Grade + (HAG+) | Sel. | Special Secretary | 16 | - | Addl. Director General (ADG) | Chief Comsnr. | |

| Higher Administrative Grade (HAG) | 25 | Additional Secretary | 15 | Principal Secretary | Principal Comsnr. | ||

| Senior Administrative Grade (SAG)/ Super Time Scale | 17 | Joint Secretary | 14 | Secretary/ Commissioner | Inspector General (IG) | Comsnr. | |

| Selection Grade (SG) | 13 | Director | 13 |

District Magistrate/ Deputy Comsnr. % |

Special Secretary | Deputy Inspector General (DIG)@ | Addl. Comsnr. |

| Junior Administrative Grade (JAG) | 9 | Deputy Secretary | 12 | Addl. Secretary | Sr. Supdt. of Police (SSP)/ Supdt. of Police (SP) | Joint Comsnr. | |

| Senior Time Scale (STS) | 4 | Under Secretary | 11 | Joint Secretary | Deputy Comsnr. | ||

| Junior Time Scale (JTS) | 0 | Asst. Secretary | 10 | Deputy Secretary | SDPO/Addl. SP | Asst. Comsnr. | |

Notes:

| ^^ | This shows the time (in years) when officers are promoted to (enter into) that particular grade. However, not in all cases and at all grades, promotions are time bound. In that sense, the year scale can be taken as showing the number of years when officers becomes eligible for promotion in the corresponding grade. Loosely, it can be said that the non-functional promotions are mostly time bound whereas the functional are vacancy based. |

| ## | The designations are mostly what would be found in a state ministries, thought it should be noted that there might be some variations in different states. |

| % | District Magistrate (DM)/Deputy Commissioner (DC) who is in charge of running a district, will be an IAS officer from any of the grades from STS, JAG and SG. |

| # | Again, designations of IPS officers are not standard, and there may be slight variations across different states |

| @@ | There is again subtle distinction within Apex scale. While pay of the officers in this scale would be the same (pay matrix level 17), but in terms of designation and hierarchy, there will be difference, and the lower one would be called a Special Secretary level, often even reporting to the Secretary level officer. For example, IPS officers in Apex Scale as DG of CRPF report to Home Secretary (an IAS officer) who is also in the same scale. |

| @ | To be correct, DIG is not a SG level post, but an intermediary level above SG and below SAG (pay matrix level 13A) which is unique to IPS, and in all probability created mainly to take care of promotions of IPS officers. |

| $$ | The designation of IRS officers looks quite neat and clean, with a distinct designation for every grade. But this may be a result of excessive obsession with hierarchy and order and may have reduced flexibility. |

| Sel. | These levels are mostly, what is called, selection posts, where officers are not promoted just on the basis seniority. Again, this is a generalization, and there may be, and are few, exceptions. |

There could be further detailing and elaboration of these features and subtle distinctions, but I think the essentially important ones which will have bearing on my discussion in this series of essays, have been covered here.

With the discussion of Homo Hierarchicus in India’s senior civil services, let me stop.

References

- Barik R R (2004): Social Background of Civil Service, Economic and Political Weekly, Mumbai, India; Vol 39, No. 7, February 14, 2004

- Dumont Louis (1981): Homo Hierarchicus – The Caste System and Its Implication; Revise Ed., University of Chicago Press, USA

- Government of India (2008): Report of the VIth Central Pay Commission, Government of India, New Delhi.

- Guha Ramchandra (2007): Indian After Gandhi - A History of World's Largest Democracy, Harper Perennial, New York, p755

- Henery Mintzberg (1979): The Structuring of Organizations, Prentice Hall, Engelwood Cliffs, N.J. pp 215-297 and “Organization Design: Fashion of Fit?”, Harvard Business Review 59, Jan-Feb 1981,

- Ministry of Labour (2003): Based on Census of Central Government Employees (2003), Ministry of Labor, Government of India and other documents; available on labour.nic.in

- Oslen Johan (2008): The Ups and Downs of Bureaucratic Organization; The Annual Review of Political Science, 2008.11:13-37,

- Pritchett Lant (2009): Is India a Flailing State? Detours on the Four Lane Highway to Modernization; Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series, RWP09-013, May 2009, pg 3

- Simon Herbert (1997): Administrative Behaviour - A Study of Decision Making Process in Administrative Organizations, 4th Ed, The Free Press, New York, Ch. 1,2 and Comments on Ch.1, 2

- Union Public Service Commission (2010): 60th (2009-10) Annual Report; UPSC, Government of India, available at upsc.gov.in

(Word Count: Approx 6700)

Comments

0 comment(s)